If you have ever held a mandrake root, you can see why it has stood apart from ordinary herbs. Mandragora officinarum is the name given to it in the old botanical texts. Mandragora comes from ancient Greek, a word tied to enclosed gardens and fields and also associated with a root shaped uncannily like a human figure. Officinarum shows that it was a plant officially kept in the storerooms of apothecaries, valued in early medicine. Over the centuries it has been regarded as a witch’s helper, a charm for fertility, a potent poison, and a spirit‑laden root with a presence all its own.

What follows is a journey through the many lives of the mandrake in folklore and witchcraft, drawn from old herbals, village legends, and the practices of witches past and present.

Ancient Roots: Mandrake in Early History

Long before the Middle Ages, people in the Mediterranean and the Near East were already weaving the mandrake into stories and rites.

In Mesopotamian texts, certain roots were linked to fertility goddesses and to oracles, as if the plant itself held a voice.

In Genesis 30:14–16, Reuben finds dudaim—widely believed to be mandrakes—and gives them to Leah. She trades them with Rachel in the hope of conceiving a child. Later Jewish commentaries treat these dudaim as potent fertility charms.

Travel south to ancient Egypt and you find mandrakes painted in tombs such as the Tomb of Anen—blue fruits offered in ritual scenes, tokens for love, life, or perhaps a safe passage to the afterworld.

Greek thinkers took note too. Theophrastus and Dioscorides described mandrake’s strange power: enough to send someone into deep, painless sleep before surgery, but dangerous in excess. In De Materia Medica, Dioscorides even distinguished male and female mandrakes, both potent and treacherous.

So even in those early centuries, mandrake was already a bridge between healing and enchantment.

A Plant That Screams: Medieval and Renaissance Folklore

By the Middle Ages, mandrake’s reputation turned eerie. It wasn’t just a root anymore, it was a being that fought back when taken.

The Scream Myth:

In manuscripts like the Hortus Sanitatis (1491) and the Pseudo‑Apuleius Herbarius, writers claimed the mandrake would shriek when uprooted. That shriek could kill you outright or drive you mad.

The Black Dog Ritual:

Old European folklore warned that a mandrake would let out a supernatural scream when it was pulled from the ground, and that this scream could kill or drive a person mad. Because of that belief, people thought you couldn’t simply dig it up yourself.The instructions went like this: you would go to the plant at twilight, loosen the earth carefully around it, and then tie its leaves or stem to a black dog with a cord. You would block your own ears with wax or wool so you wouldn’t hear the scream. Then you would step back and call the dog forward. As the dog pulled, the root would come free—its scream would strike the animal dead, sparing you.

Some versions of the story add that before doing this you had to pour wine, milk, or even blood onto the soil as a kind of offering to the spirit believed to live in the root.It is a dark and unsettling image, but these details show how strongly people once believed that the mandrake was not just a plant but a living, dangerous being, powerful enough that you had to bargain with it or trick it to take it safely.

It’s a grim picture, but it shows how alive people felt the plant to be: powerful and dangerous…

The Humanoid Shape: The “Little Man”

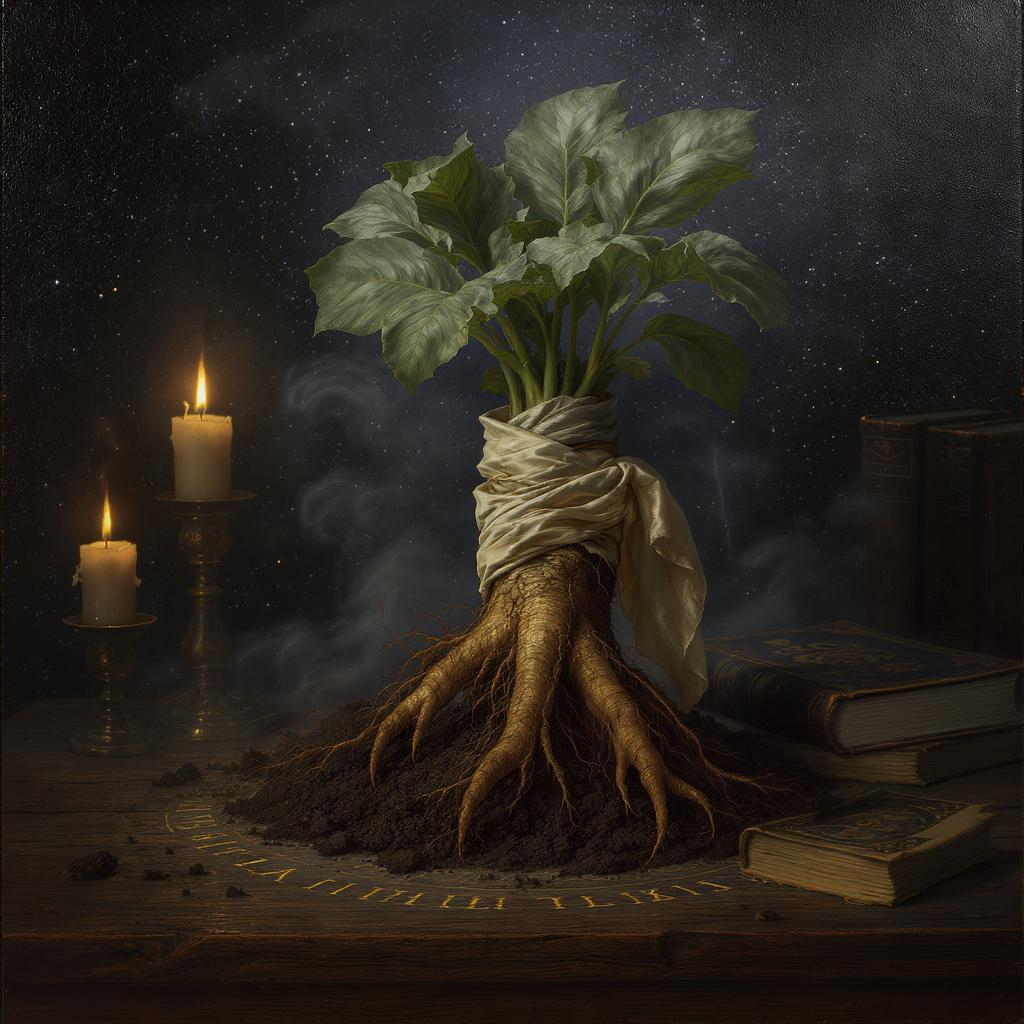

Part of mandrake’s hold on the imagination comes from how it looks. Its root often forks into legs and arms, even suggesting human features. To many, it was not a plant but a tiny person of the earth.

The word Alraun (plural Alraunen) comes from Middle High German and Old High German roots meaning roughly elf‑secret or hidden wisdom of the elves (alrūne or alrūna). In old Germanic belief, the term referred to a female seer or wise‑woman endowed with magical knowledge. Over time, this name was transferred to the mandrake root because of its uncanny, humanlike shape and its reputation for possessing occult powers, much like those attributed to the legendary Alruna women.

So when German folklore speaks of the mandrake as an Alraun, it reflects the plant’s association with hidden magic, prophecy, and the secret arts, echoing the ancient image of the witch or wise‑woman herself.

But a mandrake was never to be neglected. Folktales warned that to mistreat it, or let anyone else know you owned it, invited disaster.

Jacob Grimm, in Teutonic Mythology (1835), records families who claimed their Alraun had been kept and fed for generations, hidden in attics like a secret heirloom.

Mandrake and Witches’ Ointments

As Europe moved into the Renaissance, the mandrake slipped deeper into the shadowlands of witchcraft.

Inquisition records and folklore alike speak of flying ointments: unguents made from nightshade plants such as belladonna, henbane, datura, and mandrake, blended with animal fat and smeared on the skin.

These mixtures contain alkaloids that can cause hallucinations and sensations of leaving the body. That may explain why so many accused witches confessed to “flying through the night” or attending far‑off sabbats.The Spanish physician Andres Laguna noted confessions of women who claimed these unguents helped them travel in spirit.

In folk magic we observe how the mandrake root was always perceived as a special ingredient in sympathetic magic. It could act as a double of the witch or of a lover. In Veneficium: Magic, Witchcraft and the Poison Path, Daniel Schulke elaborates on this:

“At the center of the magical concerns of mandrake effigy-spells are enchantments for empowerment of the human body: increased fertility, sexual vigour, and attracting a sexual consort. The crudely anthropomorphic form of the root has been advanced as the reason for this, as many of the examples of mandrake effigies have pronounced phalli or vulvas?

However, certain preparations of the mandrake, especially in a fermented alcoholic form, behave as an aphrodisiac in small doses, and have had this reputation among cunning folk for cen-turies. More recently, scientific research has identified withano-lides and sterols present in Mandragora officinarum, a species which has also amassed a considerable amount of aphrodisiac lore. Curiously, many of the taboos surrounding the magical usage of mandrake fetishes demand a kind of marital, or consort relationship between the fetish and the operator, in which one pledges body and soul to the Root. Affirmation of the Pact through adoration of the fetish brings power, but neglect brings absolute ruin.” (p. 150).

A plant always perceived as possessing a living consciousness and powerful spirit, and can have a variety of uses in spellcraft due to its powerful metaphysical properties and ability to act as a vessel of power. To anchor the essence of the witch itself, or of those she wishes to enchant…

Fertility, Love, and Protection

Not all tales of mandrake are dark. In many places it was a charm of blessing.

In Italian folk magic, brides might carry a mandrake to ensure fertility. Some southern Italian traditions placed a mandrake under the bed to invite conception.

In English charms, powdered mandrake was sewn into little bags to heal sorrow or attract love. A root wrapped in cloth might be buried under the threshold of a home to guard it against thieves and wandering spirits.

The Pennsylvania German grimoire The Long Lost Friend (1820s) includes root‑based charms that echo these older European beliefs.

Mandrake in Grimoires and Folk Books

The European grimoires—those “Books of Secrets”—preserve fragments of old mandrake lore.

The Key of Solomon instructs that magical roots be harvested in the hour of Venus, under ritual purity.

The chapbook Albertus Magnus: Egyptian Secrets lists mandrake among roots that bring luck or wealth.

And in some chilling German legends, mandrakes were said to grow from the seed of a hanged man, blending death’s power with life’s.

Modern Occult and Witchcraft Traditions

In this day and age, the mandrake is still worked with by adepts of the poison path and green magick. It always approached with a reverence edged by caution. Its true toxicity is well understood, so contemporary practitioners tend to work with dried roots, carefully prepared tinctures, or even purely symbolic carvings rather than raw, fresh plants.

Some witches shape a root into a small humanlike figure, clothe it in silk, and keep it as a household guardian. Others honor the mandrake within the wisdom of Poisons, a stream of magic that seeks out the teachings of baneful plants, embracing their dangerous and transformative wisdom. Centuries pass and its power will always call to those practitioners drawn to the shadowed edges of the Green. For as long as there are hands that seek the old ways, the mandrake will whisper through root and spirit alike, offering its perilous gifts to those willing to listen. It remains a guardian, a teacher, and a mirror of our own hunger for mystery, forever entwined with the lore of witchcraft.

References and Further Reading

- Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, 1st century CE

- Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants, c. 300 BCE

- Hortus Sanitatis (Mainz, 1491)

- Pseudo-Apuleius Herbarius, 4th century CE

- Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 1989; see also “Alraune” in Oxford Dictionary of Germanic Mythology and Wiktionary entry for “Alraune.”

- Guazzo, Francesco Maria. Compendium Maleficarum. Milan, 1608

- Pennick, Nigel. The Secret Lore of Plants: Herbs, Trees, and Flowers in the Middle Ages. Destiny Books, 2001

- Schulke, Daniel. Veneficium: Magic, Witchcraft and the Poison Path. Three Hands Press, 2012

- Thompson, C. J. S. The Mystic Mandrake. Rider & Co., 1934

- Grimm, Jacob. Teutonic Mythology. 1835

- Harner, Michael. Hallucinogens and Shamanism. Oxford University Press, 1973

- Hutton, Ronald. The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford University Press, 1999

Leave a comment